JEREMY DENNIS

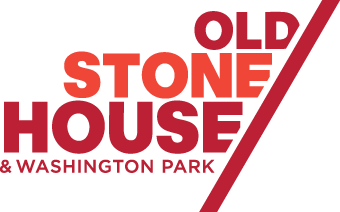

On This Site: Indigenous Landscapes Throughout Long Island (2021)

Long Island Map

On This Site is an art-based research project whose goal is to preserve and create awareness of sacred, culturally significant, and historical Native American landscapes on Long Island, New York. Through curiosity about my own origin and ancestral history as a Shinnecock Nation tribe member, I gather and combine archaeological, anthropological, historical, and oral stories to answer essential cultural defining questions: Where did my ancestors live? Why did they choose these places? What happened to them over time? Do these places still exist? To seek the answers, I research, visit, and photograph each site, documenting the change in each landscape and highlighting the everlasting connection between place and memory. These sites remain but were made invisible.

Visible on the web and in a self-published book, On This Site creates a new opportunity for self and communal reflection upon our assumptions and stereotypes regarding Indigenous and colonial shared history on Long Island. I hope that sharing this research will begin the process of communal awareness and cultural enlightenment, which leads to cultural critique, historical inquiry, and educational development. If nothing else, the project reinforces the idea that Native people existed throughout Long Island for more than ten thousand years. We are still present here today, and will continue to be here.

Visit jeremynative.com/onthissite to view the full map of Long Island and learn about additional sites.

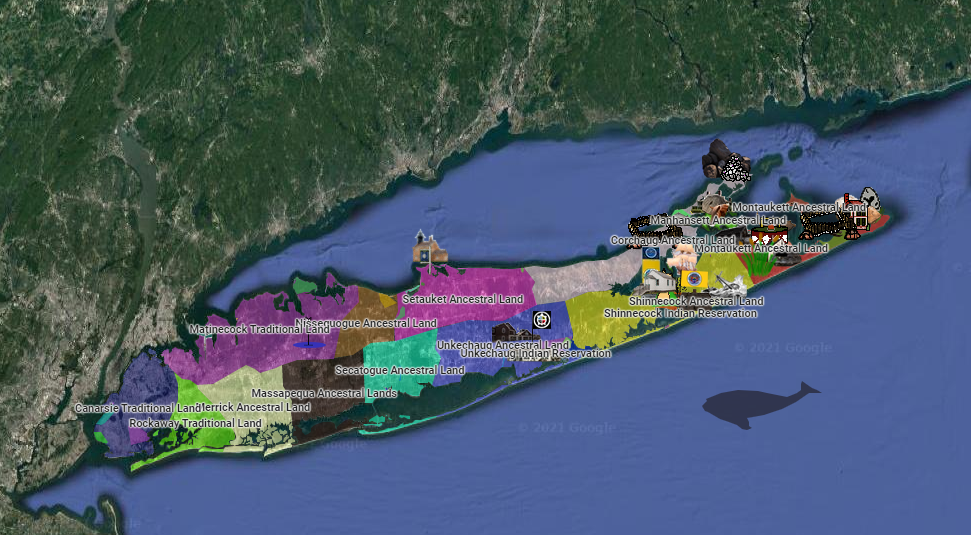

On This Site: Indigenous Landscapes Throughout Long Island (2021)

Brooklyn Map

Site 1: Werpos

Site 2: Keskaechqueren

Site 3: Winippague

Site 4: Gowanus

See more information on these four sites below.

Visit jeremynative.com/onthissite to view the full map of Long Island and learn about additional sites.

Werpos (2021)

Selection from On This Site: Indigenous Landscapes Throughout Long Island

Archival inkjet print, 16” x 20” framed

Werpos is the traditional place name for present-day Hoyt and Baltic Street in Brooklyn. There was once a village at the site, which was abandoned after the sale of Manhattan in 1626.

Visit jeremynative.com/onthissite to view the full map of Long Island and learn about additional sites.

Keskaechqueren (2021)

Selection from On This Site: Indigenous Landscapes Throughout Long Island

Archival inkjet print, 16” x 20” framed

Keskaechqueren is the traditional place name of today’s Flatlands, Brooklyn. Keskaechqueren was used as a famous council-place, as the name may translate to “a place where public meetings take place” or “the community.”

Visit jeremynative.com/onthissite to view the full map of Long Island and learn about additional sites.

Winippague (2021)

Selection from On This Site: Indigenous Landscapes Throughout Long Island

Archival inkjet print, 16” x 20” framed

Winippague is the traditional place name for what is now Bergen Island in Jamaica Bay. The alternative name is Wimbaccoe. Anthropologist William Wallace Tooker denotes that the name may translate to “a fine water-place,” from wini, “fine,” and -paug, “water-place.”

It is believed that Winippague or Bergen Island was the principal wampum manufacturing site for the Canarsie people at the time of early contact with Europeans. Arrowheads were also found on the site, which are now in the Smithsonian Institute collection near Washington, D.C.

Visit jeremynative.com/onthissite to view the full map of Long Island and learn about additional sites.

Gowanus (2021)

Selection from On This Site: Indigenous Landscapes Throughout Long Island

Archival inkjet print, 16” x 20” framed

Gowanus is the traditional place name for lands that spanned present-day Gowanus to the north down to Bay Ridge.

Visit jeremynative.com/onthissite to view the full map of Long Island and learn about additional sites.

Cigar Indian (2018)

Selection from Rise

Archival inkjet print, 16” x 20” framed

The series Rise reflects upon the ongoing subtle fear of Indigenous people in the United States. Fear, in this instance, may come from acknowledging our presence, not as an extinct people, but as sovereign nations who have witnessed and endured the process of colonization for hundreds of years and remain oppressed.

This series reflects upon the historical legacy of the Pequot War, King Philip’s War, and the inherent fear that one day, oppressed groups may rise and defend themselves. As an indigenous tribal member who has observed the aftermath of colonization, especially as member of a Federally Recognized tribe east of the Mississippi, my work in Rise approaches the concept of a future Native American uprising from a complicated perspective of military and land deed neutrality, cultural assimilation, and as a people hiding in plain sight.

Playing with recognizable zombie film and TV show iconography, Rise highlights parallels between the apocalyptic rising undead and popular misinformation of indigenous people as a vanished race.

Land Claim (2019)

Selection from Rise

Archival inkjet print, 16” x 20” framed

The series Rise reflects upon the ongoing subtle fear of Indigenous people in the United States. Fear, in this instance, may come from acknowledging our presence, not as an extinct people, but as sovereign nations who have witnessed and endured the process of colonization for hundreds of years and remain oppressed.

This series reflects upon the historical legacy of the Pequot War, King Philip’s War, and the inherent fear that one day, oppressed groups may rise and defend themselves. As an indigenous tribal member who has observed the aftermath of colonization, especially as member of a Federally Recognized tribe east of the Mississippi, my work in Rise approaches the concept of a future Native American uprising from a complicated perspective of military and land deed neutrality, cultural assimilation, and as a people hiding in plain sight.

Playing with recognizable zombie film and TV show iconography, Rise highlights parallels between the apocalyptic rising undead and popular misinformation of indigenous people as a vanished race.

Proud Boy (2018)

Selection from Rise

Archival inkjet print, 16” x 20” framed

The series Rise reflects upon the ongoing subtle fear of Indigenous people in the United States. Fear, in this instance, may come from acknowledging our presence, not as an extinct people, but as sovereign nations who have witnessed and endured the process of colonization for hundreds of years and remain oppressed.

This series reflects upon the historical legacy of the Pequot War, King Philip’s War, and the inherent fear that one day, oppressed groups may rise and defend themselves. As an indigenous tribal member who has observed the aftermath of colonization, especially as member of a Federally Recognized tribe east of the Mississippi, my work in Rise approaches the concept of a future Native American uprising from a complicated perspective of military and land deed neutrality, cultural assimilation, and as a people hiding in plain sight.

Playing with recognizable zombie film and TV show iconography, Rise highlights parallels between the apocalyptic rising undead and popular misinformation of indigenous people as a vanished race.

Garden Wonders (2019)

Selection from Rise

Archival inkjet print, 16” x 20” framed

The series Rise reflects upon the ongoing subtle fear of Indigenous people in the United States. Fear, in this instance, may come from acknowledging our presence, not as an extinct people, but as sovereign nations who have witnessed and endured the process of colonization for hundreds of years and remain oppressed.

This series reflects upon the historical legacy of the Pequot War, King Philip’s War, and the inherent fear that one day, oppressed groups may rise and defend themselves. As an indigenous tribal member who has observed the aftermath of colonization, especially as member of a Federally Recognized tribe east of the Mississippi, my work in Rise approaches the concept of a future Native American uprising from a complicated perspective of military and land deed neutrality, cultural assimilation, and as a people hiding in plain sight.

Playing with recognizable zombie film and TV show iconography, Rise highlights parallels between the apocalyptic rising undead and popular misinformation of indigenous people as a vanished race.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Jeremy Dennis is a contemporary fine art photographer and a tribal member of the Shinnecock Indian Nation in Southampton, NY. His work explores Indigenous identity, culture, and assimilation. Dennis was one of 10 recipients of a 2016 Dreamstarter Grant from the national non-profit organization Running Strong for American Indian Youth. Residencies include Yaddo, Byrdcliffe Artist Colony, North Mountain Residency, Shanghai, WV, MDOC Storytellers’ Institute, Saratoga Springs, NY, and the Vermont Studio Center hosted by the Harpo Foundation. He has been part of several group and solo exhibitions, including the Parrish Art Museum; The Department of Art Gallery, Stony Brook University; the Wallace Gallery, SUNY College at Old Westbury, NY; the Flecker Gallery at Suffolk County Community College, Selden, NY; and the Suffolk County Historical Society, Riverhead, NY. Dennis holds an MFA from Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, and a BA in Studio Art from Stony Brook University, NY. He currently lives and works in Southampton, New York on the Shinnecock Indian Reservation.

Follow him on Instagram at @jeremynative.